In this blogpost, Milla Vaha provides an analysis of state sovereignty and maritime borders with a focus on the large ocean states of the Pacific, that are “powerfully exercising their right to self-determination” through a reinterpretation of international law and statehood in the age of climate change and sea-level rise.

Statehood, as regulated by the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933), requires the state to have a defined territory interpreted as a bordered, physical landmass over which the state has control. Colonial expansion focused on annexing new lands and extracting resources and labour from these territories. The process of decolonialization allowed original occupants to reclaim land, drawing thousands of kilometres of new borders across the world.

Borders are an important part of the modern symbolic and physical embodiment of the state, creating visible and invisible boundaries between individuals, demarcating people and places and giving us exclusive identities, rights and responsibilities. Over the last few years, borders have once again become cemented through the travel restrictions imposed by various governments in the pandemic world.

Geographically, borders have been drawn between mountains and valleys, lakes, and rivers. Historically, this exercise has often been random and violent, disregarding communities living on border zones. Today, states have been formed on every piece of inhabitable land on the planet. Some are landlocked, while many have access to the sea.

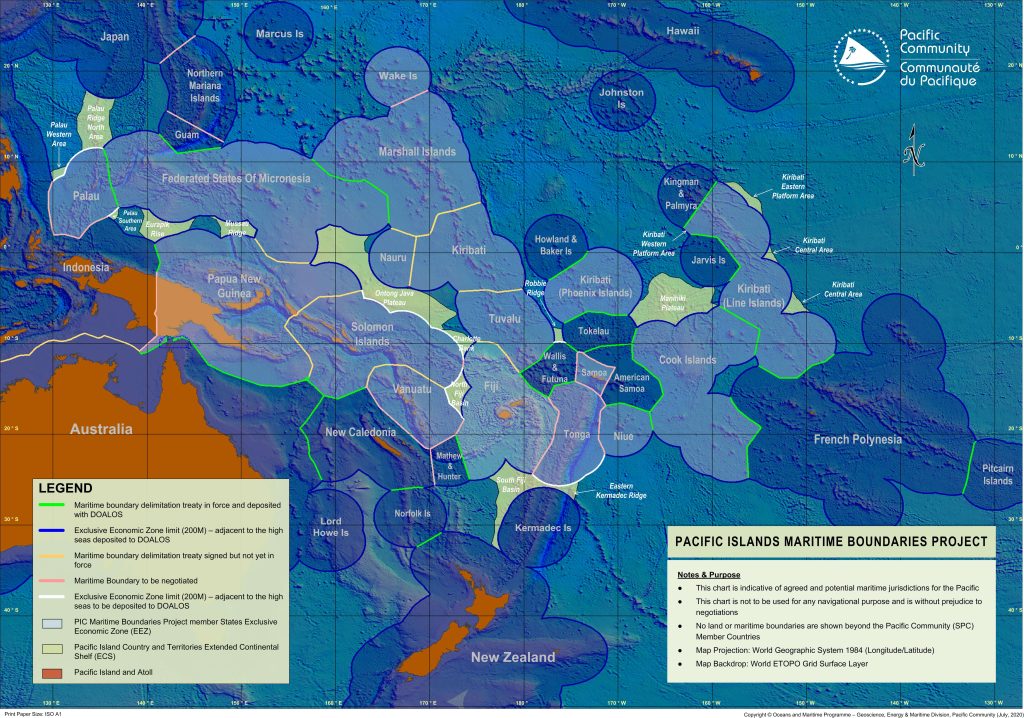

Map by Pacific Community depicting the status of Pacific maritime boundaries.

Until recently, oceans played a different role from the territories on land. The seas have been seen as spaces of freedom, commerce, exploration and voyage. The sea was not internationally regulated before 1982 – this year marks the 40th anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS). While the sea and maritime boundaries of the state have gained less attention in law and politics than territorial sovereignty on land, climate change has brought the ocean into the heart of global politics.

In 2021, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) – a regional body of South Pacific Island states, Australia and New Zealand – gave a Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-Related Sea-Level Rise. A great concern for many Small Island Developing States is that climate change will irreversibly affect their legal entitlements regarding sovereign territories. Acknowledging that the consequences of sea-level rise were not considered when UNCLOS was originally negotiated, PIF recalls the rights of island states to their maritime zones and calls for urgent collective action to secure them. According to PIF, UNCLOS ‘imposes no affirmative obligation to keep baselines and outer limits of maritime zones under review nor to update charts or lists of geographical coordinates once deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations.’

The jury is out on the interpretation of UNCLOS exercised by the Pacific Islands Forum. Future readings of UNCLOS under the shifts climate change will bring to our lived spaces, on land and in coastal areas, will surely be of interest to a broad range of scholars and practitioners in years to come. The Declaration itself is a unique initiative by the Pacific island states that have been continually active at different global forums, raising awareness of the consequences of the climate crisis to vulnerable island communities and acting as the moral voice of world politics.

In the 1990s, influential Pacific thinker and poet Epeli Hau’ofa made critical comments about the political and economic conception of ‘small island states,’ noting importantly how the language used in relation to these big oceanic states diminishes their role and status in world politics, depicting them inferior and vulnerable. This smallness and vulnerability is vividly absent from the PIF Declaration, in which the big oceanic states boldly interpret international law to their benefit, unapologetically rejecting the oft-offered reading that the current legal framework might lead them to lose their maritime zones and other assets, even their self-determination and sovereignty as states. In doing so, one could argue, the Pacific Island states are not only securing their sovereign territory at sea among themselves, but also powerfully exercising their right to self-determination and in doing so reinterpreting statehood in the global arena.

It is commonly argued that world politics is obsessed with the state, and I for one am guilty of such a preoccupation. The reason I now find myself at the University of the South Pacific is a result of years of thinking about what the state is and what kind of agency it has. I have studied the genealogy of the state from early Greek philosophy to modern political theory and tried to understand the complexities surrounding an entity that in many ways is imaginary, yet must act as if it was real. The interplay between the territory on land and at sea has added an interesting layer to that work, a layer that enables an attempt to explain the meaningfulness of maritime existence of the state in the Pacific context.

In my recent book I argue that the difficulty of international politics to grasp territoriality beyond land might have something to do with our colonial mindset, with a focus on certain key characteristics of the modern state – a permanent population, defined territory (on land), monopoly of use of force. Of course, it makes sense to require a political community to have some territory, as it is the case that we unlikely can ever live on floating arrangements such as boats for an extended period. At the same time, our conceptions of the state are too fixated with territoriality on land, forgetting or ignoring most of this planet. Preoccupation with land overlooks the fact that for many states – especially island states – most of their territory is in fact formed by water and much of the identity of their citizens is inherently tied to the idea of existence at sea.

Photo by Håkon Larsen.

The PIF Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones plays within the traditional framework of territoriality. It attempts to secure the existing maritime boundaries of island states against the damaging effects of climate change. The Declaration re-interprets the existing international law, rather than aiming at developing new laws in a political context in which conflicting national interests would not allow re-opening the text of UNCLOS itself. Therefore it is an exercise of sovereignty in a traditional sense.

At the same time, it stretches the law to new conceptions of sovereign right to the ocean. It emphasizes the role of the ocean in the self-determination of these entities, forcing the rest of the world to acknowledge and recognize their spatial existence at sea. The Declaration serves as a tool to unpack the contemporary ‘key’ characteristics of the state – especially regarding territoriality – beyond the statehood on land and is therefore an important initiative at the time of climate crisis.

By taking steps as a region to guarantee their maritime borders, the Pacific island states have exemplified true guardianship and agency. They have contested notions of smallness and vulnerability, and taken the first steps necessary to guarantee their future existence.

What must follow is worldwide recognition and enhanced ambition to safeguard the rights – the sovereign rights included – of political communities that are put at risk by climate change.

Acknowledging the importance of oceans to the self-determination of island states is vital in this regard.

Photo by Håkon Larsen.

Dr. Milla Vaha is a Lecturer in Politics and International Affairs at the University of the South Pacific and an adjunct research fellow at Island Lives, Ocean States project. In the project, her focus is on the conceptual and normative elements of oceanic statehood as well as the rights and responsibilities of Pacific island states at the time of climate crisis. She wishes her academic work to further strengthen the moral voice of island states at global arenas.

Dr. Milla Vaha is a Lecturer in Politics and International Affairs at the University of the South Pacific and an adjunct research fellow at Island Lives, Ocean States project. In the project, her focus is on the conceptual and normative elements of oceanic statehood as well as the rights and responsibilities of Pacific island states at the time of climate crisis. She wishes her academic work to further strengthen the moral voice of island states at global arenas.